0005: Window Size

I’ve prepared two code files this time, a straight set-the-size example and another with a button for resetting size. Both examples are based on the OOP test rig window.

Pre-Size a Window

Now let’s talk about the next code example.

Window Resized

There’s only one new line of code here and it appears in the TestRigWindow’s constructor:

setSizeRequest(300, 400);

You may wonder why size is being requested instead of demanded, but that’s a question for the original GTK+ devs and it really doesn’t matter, anyway.

The numbers are, of course, the x and y dimensions of the window we’re opening.

Simple. Now let’s look at something a bit more interesting…

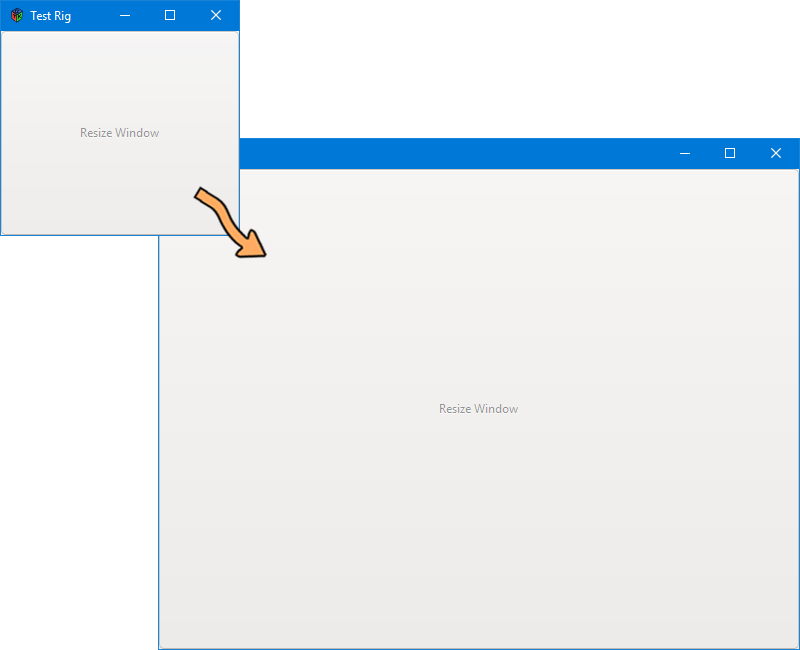

Size a Window on the Fly

In the second code file, instead of requesting a size, we demand it:

setDefaultSize(640, 480);

Why? Sometimes you wanna override the window manager (POSIX and POSIX-like operating systems) and sometimes you don’t. The philosophy regarding when ‘to’ and when ‘not to’ is beyond the scope of this blog (mainly because I have no freaking idea).

But the interesting part comes further down where I’ve defined a class called ResizeButton:

class ResizeButton : Button

{

this(MainWindow window)

{

super("Resize Window");

addOnClicked(delegate void(Button b) { resizeMe(window); });

} // this()

void resizeMe(MainWindow window)

{

int x, y;

window.getSize(x, y);

writeln("x = ", x, "y = ", y);

if(x < 640)

{

window.setSizeRequest(640, 480);

}

else if(x > 641)

{

writeln("Minimum size is now set. You can shrink it, but not below the minimum size.");

window.setSizeRequest(640, 480);

}

}

} // class ResizeButton

Right off the bat, the constructor takes its parent window as an argument. That’s so we can use one of the window’s functions (I’ll get to that in a minute). The window argument could also be defined as type TestRigWindow.

And after the call to super() to create the window, the window argument is passed along to the callback function.

The resizeMe() Callback

Here we dabble in a little contract programming, yet another of the D language’s cool features. Back in my C days, I often wanted to return more than one value from a function, but of course, that was impossible at the time. The only recourse was to either rewrite the code as two functions or use a struct to hold multiple values.

But D has contracts and that means we can have a function definition like this in the Window class:

public void getSize(out int width, out int height)

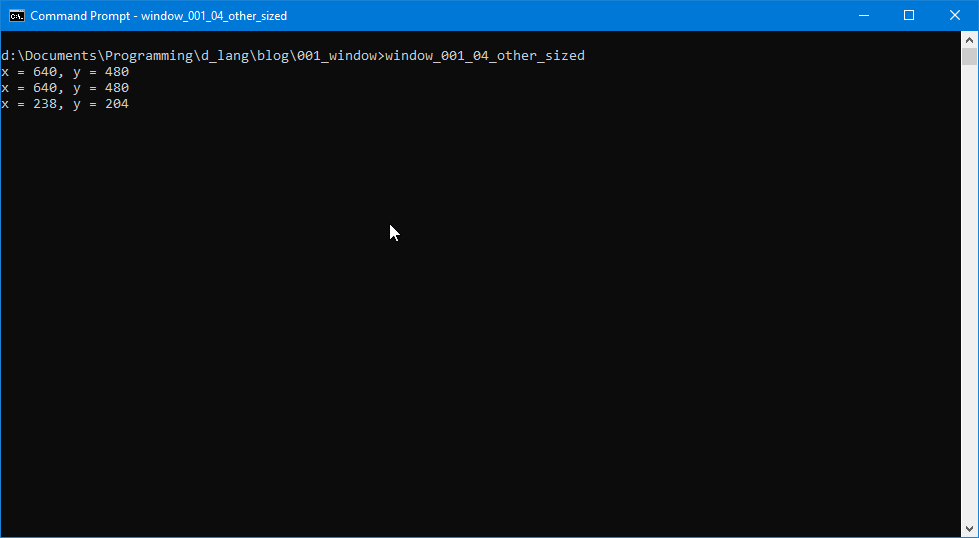

You’ll notice that getSize() returns nothing. But looking a bit closer, the ‘out’ keyword appears in front of both function arguments. That means that we can define two variables, x for width and y for height, and then pass them along to getSize() and when the function returns, the calling function has access to the new values set in getSize(). It’s more or less the same as passing the variables in by reference in C (or in other words, passing the variable’s addresses instead of the variables themselves). But D gives us this more formalized way of doing it which makes this possible:

int x, y;

window.getSize(x, y);

Then we do something if-fy (and else-y), setting the window size with a request this time. In fact, if we use setDefaultSize() in these callbacks, nothing happens. So we have to use setSizeRequest().

NB: Use of the keywords in, out, and ref in function definitions can be thought of in the following terms:

in: the variable’s value is set by the caller and cannot be changed by the called function,out: the variable’s value is set by the caller and can be changed by the called function, but if the function is called repeatedly, the value is reset before each callref: the value is set by the caller, can be changed by the called function, and retains its new value even if called repeatedly.

And something else interesting happens here. GTK deals in minimum sizes, not maximum or absolute sizes, therefore we can set a window’s minimum size, but that’s it. And that affects the behaviour of our example.

Once the example is running – before clicking the Resize Window button – grab the window’s size widget and make the window smaller. No problem. Now click the Resize Window button and the window goes back to it’s original size.

But – and here’s the interesting bit – if you try to make the window smaller at this point, it refuses.

But-but, if you now make the window larger and click the button again… well, nothing seems to happen… until you grab the size widget and make it smaller. It works. The window can once again be sized smaller than its original size.

So, behaviour-wise, as long as the window is smaller than it was to begin with, clicking the button sets a minimum size. As long as the window is larger than the original size, clicking the button removes the minimum size limitation.

This line reveals the magic:

window.setSizeRequest(-1, -1);

Passing -1 to both unlocks the minimum sizes for x and y, allowing us to freely resize the window again.

That’s all for today. Next time, I’ll talk about window positioning and bring in another OOP concept, the interface. Until then, happy D-coding and may the widgets be… you know.

Comments? Questions? Observations?

Did we miss a tidbit of information that would make this post even more informative? Let's talk about it in the comments.

- come on over to the D Language Forum and look for one of the gtkDcoding announcement posts,

- drop by the GtkD Forum,

- follow the link below to email me, or

- go to the gtkDcoding Facebook page.

You can also subscribe via RSS so you won't miss anything. Thank you very much for dropping by.

© Copyright 2025 Ron Tarrant